Kanban cards: Definition, anatomy, templates, and best practices

A Kanban card is a task that’s been dragged into the light. It’s one work item, made visible, that moves across your board from start to finish with an owner and details attached.

This guide is for teams using or considering a Kanban system who want better cards that keep work visible and help limit work in progress (WIP) so the flow stays smooth.

A brief history of Kanban

Before Kanban boards showed up in software teams, they lived on a factory floor in Japan. At Toyota in the 1950s, industrial engineer Taiichi Ohno studied how supermarkets restocked shelves only as customers bought items. He adapted that idea into a card system on the production line: when parts reached a set threshold, a card would move and signal just-in-time replenishment, rather than building up piles of inventory.

Swap car parts for tasks, and you have a modern Kanban board. Today, a Kanban card represents a single piece of work, and the Kanban board stands in for the production line. As cards move across columns, teams can see real flow, spot blockers early, and keep work in progress (WIP) at a sustainable level so projects finish faster instead of stalling halfway.

Anatomy of a Kanban card

A Kanban card is basically a mini control center for a piece of work. To keep it functional, it helps to think of it in two layers:

- The face, for fast scanning

- The back, for doing the work

The face of the card (visual information)

The face is what you see as you scan the Kanban board. In a fraction of a second, it should answer:

- What is this?

- Who owns it?

- How urgent is it?

Most teams surface a clear title, the assignee, a due date, and a simple priority signal right on the card. Many will also add one or two labels that instantly indicate which world this task belongs to, such as a release name, customer, or project.

The important part is restraint. If everything is visible at a glance, nothing stands out.

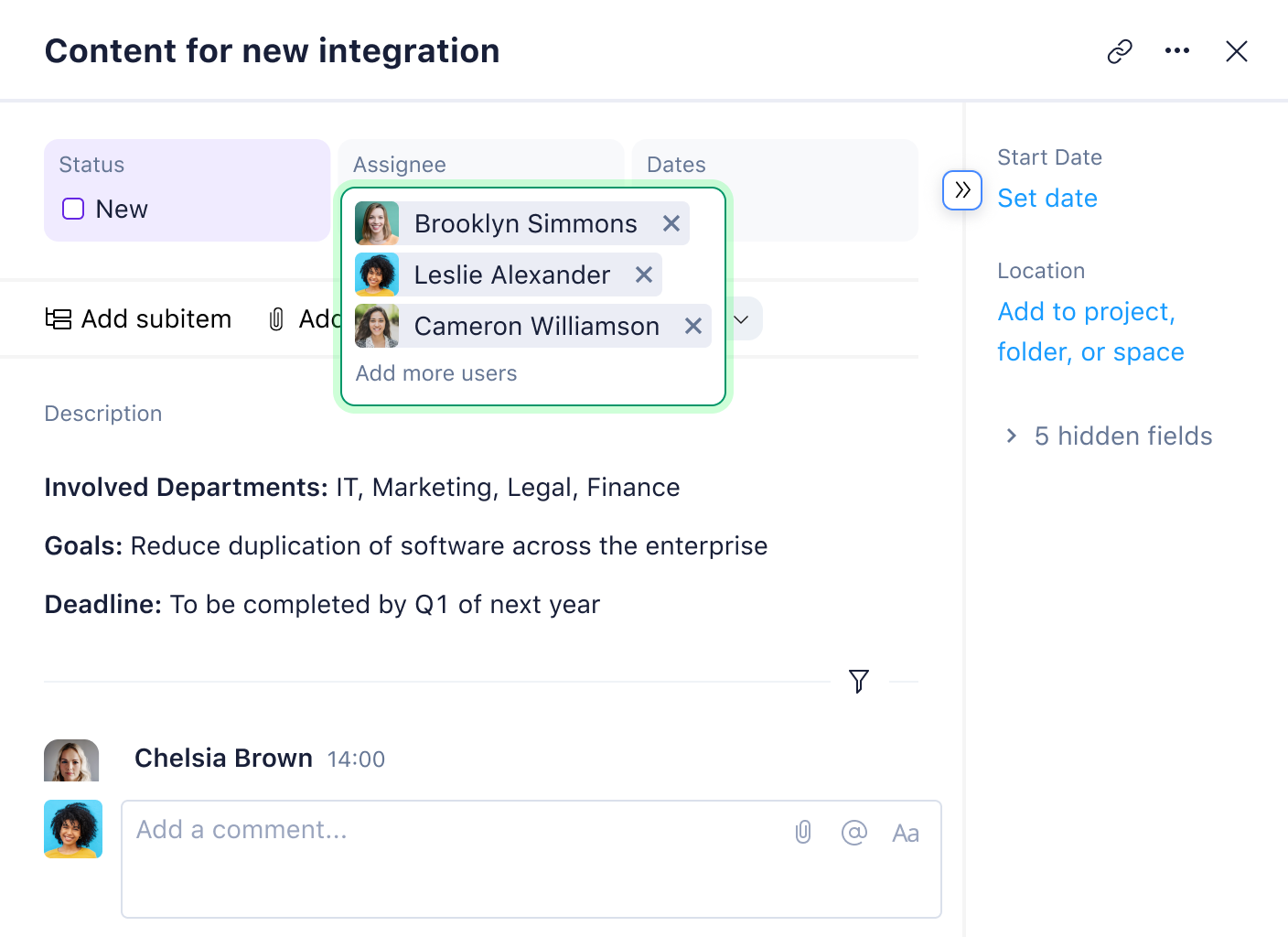

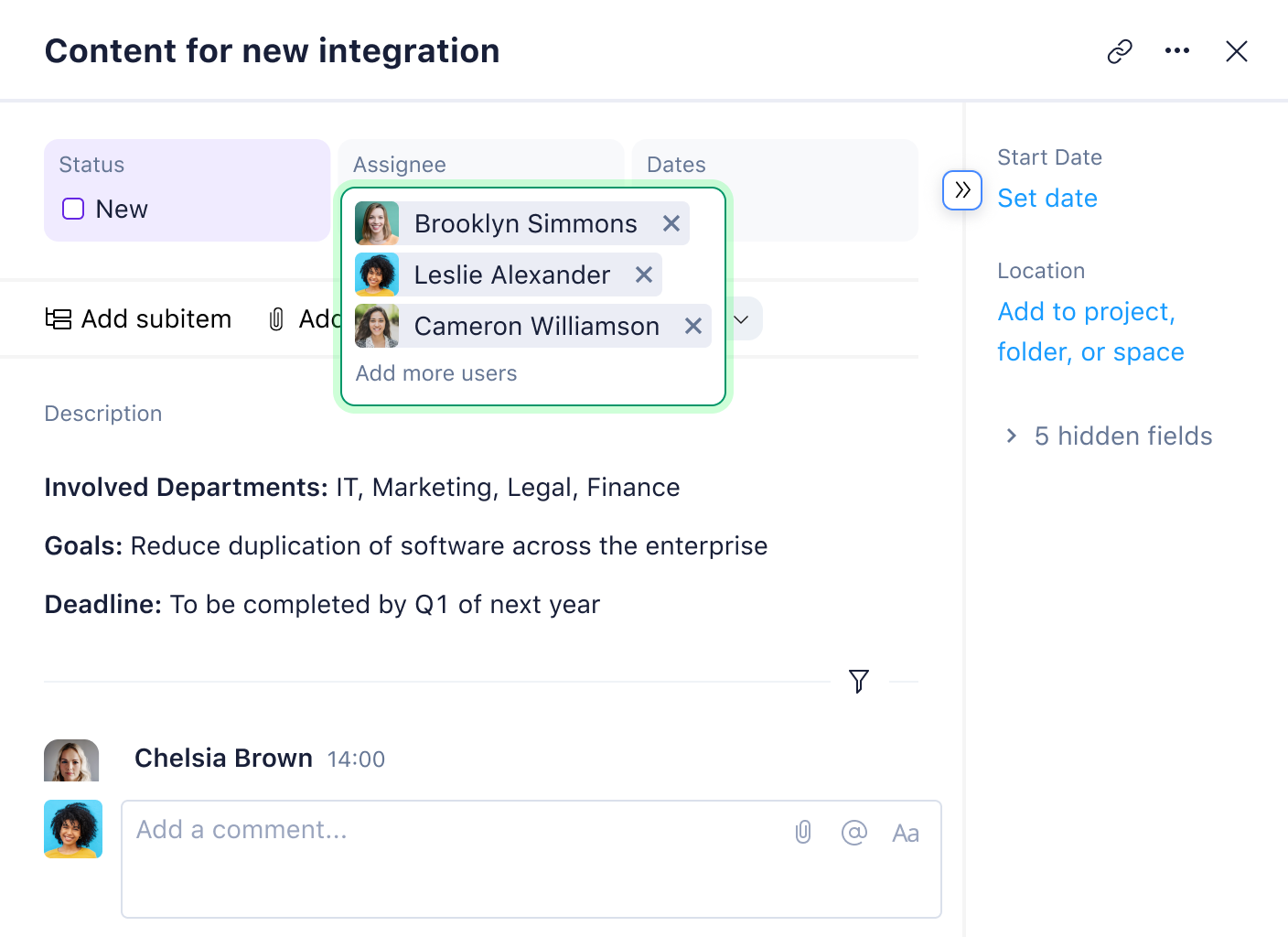

Back of the card or digital card details (detailed information)

Once someone clicks into the Kanban card, the back takes over. This is where context lives. It should have the full description, any acceptance criteria, and the story behind the work.

- Checklists or subtasks break vague requests into a sequence of concrete actions.

- Dependencies show what this work is waiting on or what will break if it slips.

- Attachments keep specifications, mockups, or recordings tied to the task, rather than being buried in chat history.

- Comments and activity history record questions, decisions, and changes so you can reconstruct what happened later.

How Kanban cards work on a board

Once you’ve designed a solid Kanban card, the real magic is what happens as it moves across the Kanban board. Kanban runs on pull, not push. Instead of someone upstream assigning work and pushing it into people’s laps, team members pull the next card when they actually have capacity.

For example, a designer finishes one task, looks at the “ready for design” column, and then pulls the top-priority card.

This is where WIP limits come in, and why they belong on columns. When you put a WIP limit on a column, you’re basically saying that this stage can only handle a certain number of items at once. If the limit is five and the column already has five cards, nobody can start something new. Instead, they’ll help finish what’s already in motion, clear blockers, or support whoever is stuck.

Each card is also a data point for lead time and cycle time. Lead time tracks how long it takes from the moment a request enters the system until it is delivered. Cycle time focuses on the period from when active work begins to when the card reaches the “done” column.

In practice, this might look like: A landing page hero image card moves from design when the layout is approved, into development while it’s implemented, and then onto testing once the new image is ready for QA in a staging environment.

Required and optional Kanban card fields

Every Kanban card needs a few required fields before being put on the board:

- Title

- Owner

- Short description

That’s enough to let someone know what it is and who owns it. For time-sensitive work, add a due date as a near-mandatory field so the team can see what’s at risk.

Everything else is optional and should be added only if it changes a decision. Some optional fields could be:

- Assignee: Who’s going to complete the task

- Priority: How urgent or important is it compared to other work

- Due date: The estimated completion date

- Tags: Keywords for grouping and filtering (customer, area, release, etc.)

- External link: Direct link to a spec, doc, or external system

- Checklist/subtasks: Smaller steps to track progress inside the card

- Dependencies: Related tasks that block another one

- Task ID: Unique reference for reporting or cross-tool tracking

- Comments: Updates, questions, and decisions in one place

- Difficulty points: Team-defined effort or size estimate

Kanban card sizing

Another optional Kanban card field some teams include is card size. Card size is a relative measure of how big a piece of work is compared to other work on your Kanban board. The keyword is relative. The team defines the card size, and there are several methods for measuring the size of Kanban cards.

Common sizing patterns:

- T-shirt sizes: XS, S, M, L, XL

- Fibonacci numbers: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, etc.

The team decides what those values roughly mean. For example, S might be something you can do in one sitting, while L will take a few days.

To keep terms straight:

- Size is largely determined by relative scope and complexity. How big does this feel compared to other work?

- Effort is about workload. How much human energy will this realistically consume?

- Story points (in Agile teams) are a specific unit that bundles effort, complexity, and risk into a single number.

Making priority visible

If someone has to open the Kanban card to figure out how important it is, you’ve already lost time. A simple pattern is to use color labels (for example, red for urgent, yellow for standard, green for improvements) so the board instantly shows where attention is needed.

If your workflow is more advanced, define classes of service and tag cards accordingly, such as:

- Expedite

- Fixed date

- Standard

- Improvement/maintenance

Whether you use colors, labels, or both, when someone is ready to pull the next card, they can instantly see how fast it needs to move.

Kanban card examples

Seeing concrete cards in context makes Kanban boards a lot easier to copy and adapt. Here are two simple patterns you can lift for your own team, one digital and one physical.

Digital Kanban card example

Picture a Kanban board in your work management tool with columns for “backlog,” “in progress,” “review,” and “done.” A product launch card on that board might look like this on the face:

- Identify buyer persona

- Owner shown with an avatar

- Low priority label

- Due May 28

On the back, sketch a tight brief that spells out who this persona might be, what keeps them up at night, and how those insights will sharpen the launch story, then tuck in a checklist for interviews or surveys, plus a link to the working persona doc. Let the comments stream carry quick notes after each customer conversation, so the card slowly turns into a living snapshot of the audience you are about to launch to.

Here is a video example that goes into more detail:

You can pair this section with a simple digital card mockup and a Kanban card template file in editable format, so readers can duplicate the structure in their own workspace.

Physical Kanban card example

For physical Kanban cards, you can keep things even lighter. Use one sticky note per task and write a compact set of fields:

- Top line with a short task name, for example, “Webinar landing page”

- Bottom line with owner initials and a due date

- Small corner markers for priority or team, such as a colored dot or quick tag

If your team prefers more structure, you can print a sheet of blank Kanban cards with boxes for title, owner, due date, and WIP lane, then stick those to your board instead of plain sticky notes.

Metrics you unlock through Kanban cards

When every piece of work lives on a card, the board stops being a status wall and starts acting like a measurement tool. Here are some metrics worth tracking:

- Lead time is how long a card takes from the moment it appears on the board until it is done.

- Cycle time looks only at the stretch where someone is actively working on that card.

- Throughput simply counts how many cards your team finishes in a given time frame.

- Blocked time, or blocked work, covers the periods when the card is stuck and cannot move forward.

For those metrics to be meaningful, card habits have to be consistent. Once that rhythm is in place, the timestamps tell you where work slows down and whether your changes are actually improving delivery speed.

For a wider view, a cumulative flow diagram gives a single chart of how work builds up and clears across columns over time, and this section should link to a deeper guide that explains how to read and act on that chart.

Kanban card use cases by team type

Kanban cards are flexible by design, but teams get the best results when they fine-tune the fields to match their own work. This way, the core structure stays the same while the details shift to match how different teams actually deliver.

Software development teams

For software teams, a Kanban card often behaves like a lightweight user story. Fields that matter most tend to be a clear title, assignee, status, priority, size, and a few focused tags such as component, platform, or environment. Links to specs, design files, or an issue in your code repo sit on the back of the card, along with acceptance criteria and a short checklist for implementation and testing.

One simple policy that helps is that nothing should move into “in progress” until the card has a defined owner, acceptance criteria, and a size value. That small guardrail keeps half-baked work from entering the stream and protects cycle time from ballooning.

Marketing teams

Marketing teams use Kanban cards to track campaigns, content, and experiments as they move from idea to live. Here, fields such as campaign name, channel, owner, due date, and class of work (for example, launch, always-on, or experiment) do most of the heavy lifting.

On the back of the card, you typically see a short brief, a link to the creative folder, and a checklist that mirrors the approval path. A practical policy for these teams is to require that no card moves into “ready for review” unless the brief, target audience, and tracking plan fields are filled in. Creative and review cycles move faster when everyone can see what the asset is supposed to achieve before they weigh in.

Operations teams

Operations teams lean on the Kanban card system to manage requests, incidents, and recurring processes. The fields that quickly prove their worth are requester, impact level, location or system, due date or Service Level Agreement (SLA) target, and class of service.

Many teams also add a simple impact description and a root cause field on the back of the card. A helpful policy here is that any incident card must have its impact and SLA fields set before it can move out of triage. That way, the board reflects real urgency instead of whoever shouted loudest, and follow-up work can be better prioritized.

On digital Kanban boards, each card should cover a single, clear piece of work, not a mini-project. If it requires a long scroll, it should be split. On physical boards, use sticky notes or index cards that are large enough to display a short title, owner, and date, so that people can read them from a few steps away.

Teams work best with only a handful of active cards per person, so more items actually finish instead of stalling midstream. WIP limits sit on columns because bottlenecks occur in stages, such as “in progress” or “in review,” and capping those stages forces the team to complete existing work before taking on new tasks.

A Kanban card is the unit that moves across the board, while a user story is a way of describing the work and its value. Most teams simply put the story inside the card so the card handles flow and the story handles context.

Yes, but it works best as a tracker that links to smaller delivery cards rather than something people actively work on. If you push a whole epic through the board as one card, lead time and flow metrics become noisy, so it’s best to break the epic into smaller cards.